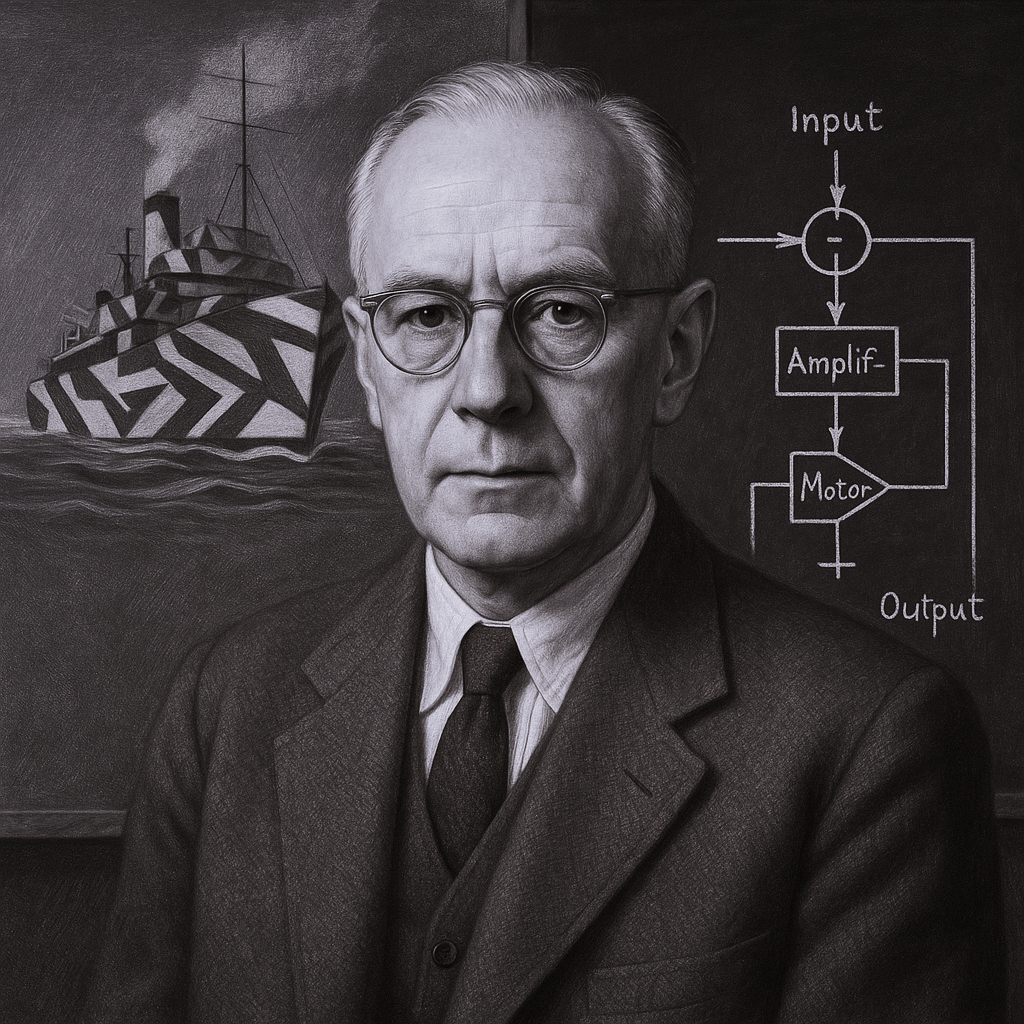

Norman Wilkinson (1878–1971) was a painter who approached war with the instincts of an artist and the clarity of a strategist. Confronted with the silent threat of submarines beneath the waves, he turned not to invisibility, but to bewilderment. His invention of dazzle camouflage transformed warships into bold, fragmented spectacles—each a kinetic canvas of broken geometry, designed to fracture outlines, disrupt perception, and scramble the delicate triangulations of enemy rangefinders. Every vessel became a riddle in motion, a shifting mosaic of lines and shadows where form dissolved into uncertainty, forcing the act of targeting itself into hesitation.

In 1914, as the first camouflaged military vehicles rolled through Paris, Gertrude Stein and Pablo Picasso observed the spectacle. Picasso, astonished, exclaimed, “Yes, it is we who made it. That is Cubism.” This moment revealed a curious symmetry already woven into the fabric of events: Wilkinson’s dazzle, born of military necessity, inadvertently mirrored the fractured geometries of modernist art. Art and warfare, perception and deception, wove themselves into a co-evolutionary braid, folding aesthetic abstraction into technical necessity, and technical necessity back into cultural form. In this constructive entanglement, something subtle emerges: that nonlinear creativity and linear mechanism are not necessarily opposing forces, but resonant harmonics of the same underlying structure—each modulating the other, each hinting that every control system begins in perception, and that to shift perception is, quietly, to shift control.

Categories

Dazzle