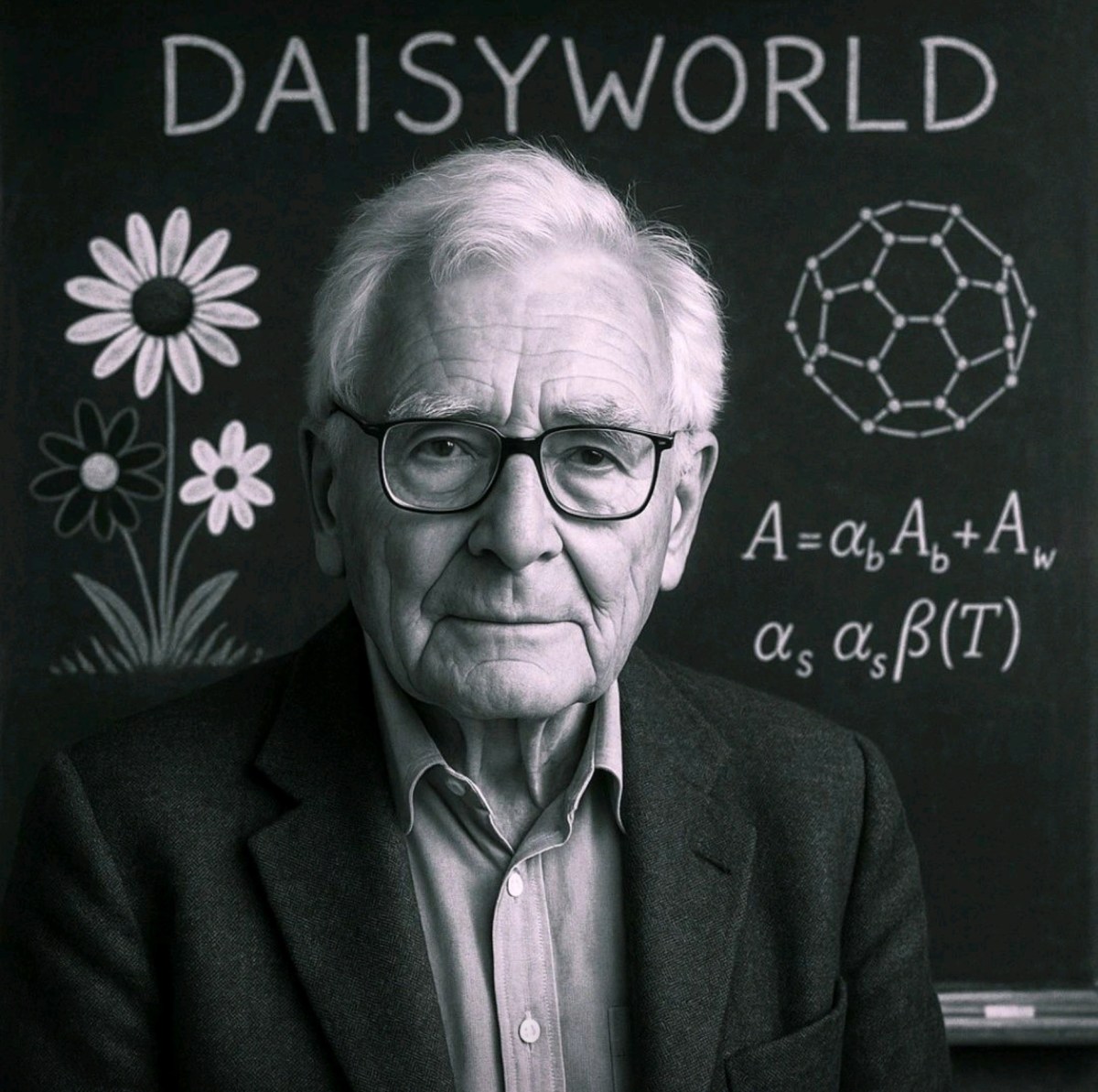

James Lovelock (1919–2022) was as pioneering as he was resisted. Uniquely famous for proposing the Gaia hypothesis—the idea that Earth behaves as a self-regulating system—he faced deep scepticism, dismissed by many as mystical or unscientific. Yet it was Daisyworld, his elegant simulation of a planet populated by simple black and white daisies, that provided a critical proof of concept. Through this stripped-back model, Lovelock demonstrated how life could regulate a planet’s temperature, not by design or foresight, but through feedback inherent to the system itself. The beauty of Daisyworld lay in its simplicity: a minimal ecosystem whose emergent properties challenged entrenched assumptions about life’s role on Earth, and by doing so, quietly rewired the conversation around planetary homeostasis.

What’s striking, in retrospect, is how many of the tools, models, and ways of thinking that could help guide us through today’s climate crisis already exist. The resistance Lovelock faced mirrors a deeper phenomenon: that new ideas, especially those with paradigm-shifting implications, are often resisted not just institutionally or politically, but psychologically. Systems define themselves by their boundaries; a novel thought destabilises those edges, forces a rearticulation of identity. In this sense, resistance to solutions isn’t purely ignorance or malice—it’s the system recognising the cost of transformation. Daisyworld was more than a simulation; it was a metaphor for the interplay between difference, adaptation, and survival—a quiet precursor to the understanding that our most powerful tools might already be in front of us, awaiting the #courage to let them reshape us.