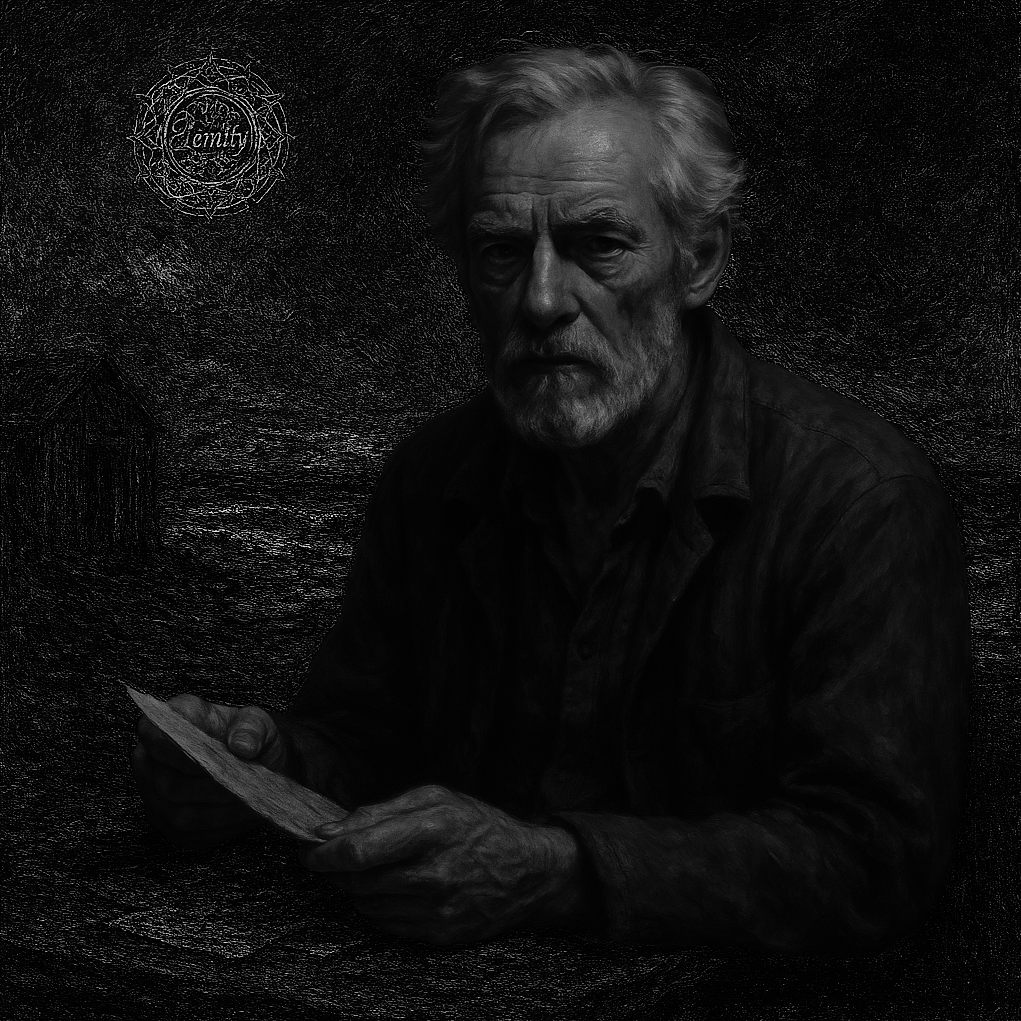

He lived in a shotgun shack by the sea, patched with tin and leaning under the wind. The tide was his only clock, the gulls his only critics. He fished enough to eat, carried crates at the dock when it was needed, and spent his nights hunched over scraps of paper, writing lines that never tried to be finished. His words circled the same themes: mortality, eternity, nothingness, time. Not to define them, not to build systems, but to test the feel of them, the way one tests the edge of a blade.

He called himself no philosopher. He had no interest in universities, journals, or conferences. Academic philosophy seemed to him like men arguing about maps while refusing to step outside. He had no patience for their careers in cleverness, their tidy disputes fenced by citation. To him, philosophy was not a profession but a necessity — the task of staying awake in a world bent on sleep.

At night, he thought of Arthur Stace chalking “Eternity” across the pavements of Sydney, a sermon in one word. He thought of Bodhidharma facing a wall for nine years, stripping thought bare until nothing was left but the void itself. He thought of the monks who spent weeks shaping sand into mandalas only to sweep them away in a single breath. These, to him, were philosophers. Not by degree, not by affiliation, but by the refusal to look away.

He saw that mortality and eternity were not enemies but mirrors. Each inflated the other, each gave the other weight. Death gave shape to life; eternity gave depth to the moment. Between them was the present — fragile, fleeting, a wave breaking and reforming again. He lived inside that wave, and his shack by the sea was only its temporary frame. The villagers thought him odd, maybe mad, but he did not care. He was not writing for them, nor for himself, but for the silence that comes after erasure. He smiled when the tide washed his scraps away, because that was the message: nothing holds, and that is what makes it worth holding.