Dating apps don’t sell love. They sell the chase. Their business model only works if most people fail to find lasting relationships. A happy couple deletes the app and disappears from the revenue stream. That means personal, social, even biological success—stable intimacy, family, belonging—represents commercial failure. So the platforms are designed to keep you searching. Studies show they provide access but not better matches (Finkel et al., 2012), that people mostly aim “upward” and get rejected (Bruch and Newman, 2018), and that too much choice leaves users dissatisfied even when they pick someone (D’Angelo and Toma, 2017). In short, the churn is the point.

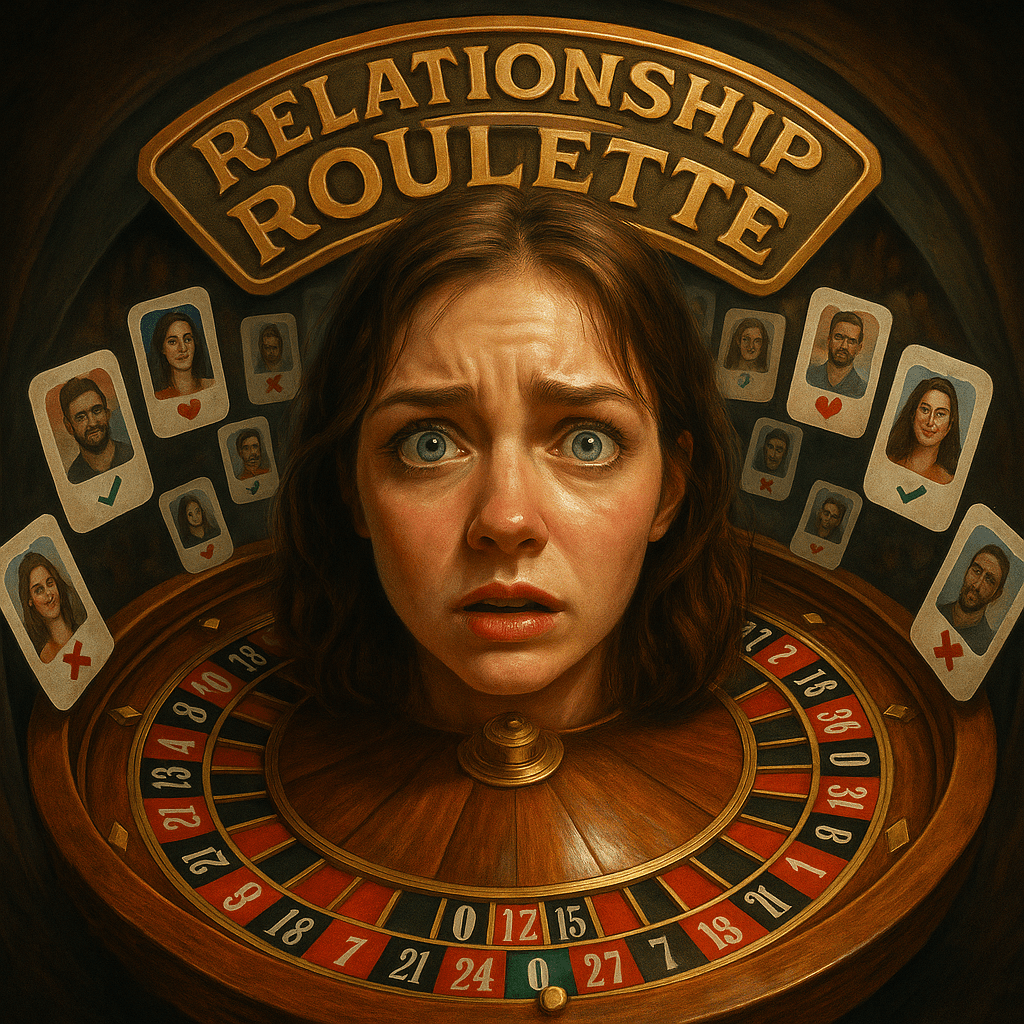

It’s not so different from gambling. Slot machines work by making loss the norm and sprinkling in just enough wins to keep players hooked. Swiping is the same: each flick is a small wager, most of which come up empty, but the near-misses drive you back for more. Researchers have found compulsive, addiction-like patterns in swiping (Orosz et al., 2018). Designers openly use persuasive techniques that pair easy actions with unpredictable rewards (Fogg, 2003). If the odds of lasting success were high, the business would collapse. So intimacy is kept liquid (Bauman, 2003), feelings commodified (Illouz, 2007), and technology positioned as the gatekeeper of connection (Turkle, 2011). The result is a marketplace of longing, where we keep rolling the dice not to win, but to keep playing.

References

Bauman, Z. (2003) Liquid Love: On the Frailty of Human Bonds. Cambridge: Polity.

Bruch, E.E. and Newman, M.E.J. (2018) ‘Aspirational pursuit of mates in online dating markets’, Science Advances, 4(8), eaap9815.

D’Angelo, J.D. and Toma, C.L. (2017) ‘There are plenty of fish in the sea: The effects of choice overload and reversibility on online daters’ satisfaction with selected partners’, Media Psychology, 20(1), 1–27.

Finkel, E.J., Eastwick, P.W., Karney, B.R., Reis, H.T. and Sprecher, S. (2012) ‘Online Dating: A Critical Analysis From the Perspective of Psychological Science’, Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 13(1), 3–66.

Fogg, B.J. (2003) Persuasive Technology: Using Computers to Change What We Think and Do. Boston: Morgan Kaufmann.

Illouz, E. (2007) Cold Intimacies: The Making of Emotional Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity.

Orosz, G., Benyó, M., Berkes, B., Nikoletti, E., Gál, É., Tóth-Király, I. and Bőthe, B. (2018) ‘The personality, motivational, and need-based background of problematic Tinder use’, Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(2), 301–316.

Turkle, S. (2011) Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other. New York: Basic Books.

One reply on “Relationship Roulette”

Our embodied, emotional experience has been weaponised against us.

True, too.

LikeLike