The institutions that claim to be the guardians of knowledge—universities, governments, large corporations—have all become deeply entangled in their own logic of continuity. Universities in particular once positioned themselves as sanctuaries for critical thought, but the reality today is closer to Stafford Beer’s observation in Platform for Change (1975): organizations tend not to innovate, they reproduce. The pursuit of tenure, funding cycles, and bureaucratic recognition ensures that scholars and administrators alike sustain the same structures, often under the guise of novelty. This is not accidental. It is systemic recursion: institutions exist to perpetuate their own conditions of existence.

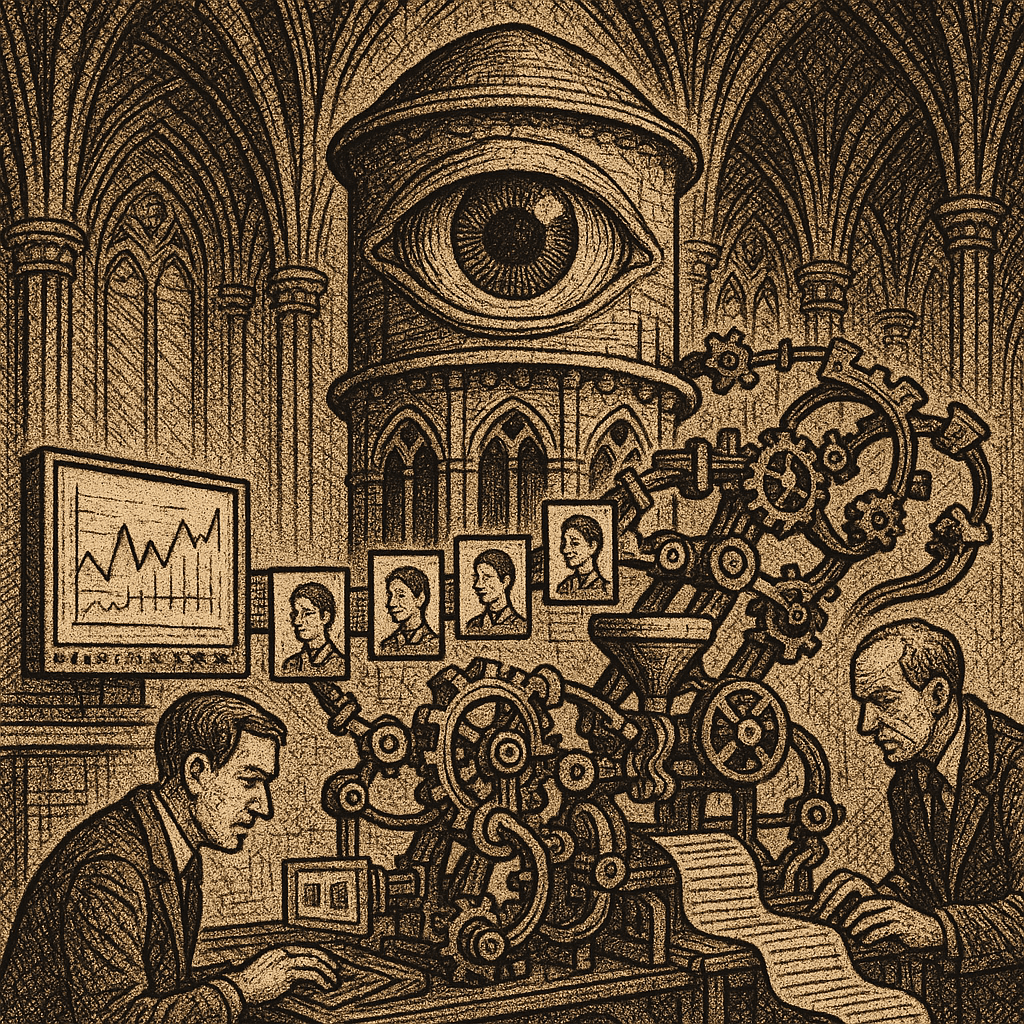

The consequence is that universities produce only fragments, small islands of discourse, rarely joined to any wider effort at change. Michel Foucault pointed to this in Discipline and Punish (1975), showing how knowledge systems become technologies of control, reinforcing authority rather than destabilizing it. The irony is that the same rhetoric of “critical inquiry” or “making the world a better place” is used as cover for entrenching the very system that resists transformation. The banners proclaim improvement, while the mechanisms quietly enforce stasis. Governments are much the same: they survive by absorbing dissent into procedure, ensuring turbulence never rises to systemic reconfiguration.

This structural inertia is not neutral—it shapes politics, technology, and belief. Systems theorists like Niklas Luhmann (Social Systems, 1984) described communication not as messages but as recursive operations that reproduce the system itself. That insight is visible everywhere: public discourse about immigration, about climate, about technology. The form of conversation is less about resolution than about ensuring the continuation of conversation itself. Hence why political narratives lean so heavily on scapegoating or manufactured threats: simple rules, repeated at scale, generate resilient patterns that bias reproduction towards sameness. The system does not aim to change; it aims to persist.

Technology has accelerated this dynamic. Universities have been swallowed by it—learning platforms, administrative dashboards, algorithmic assessments—yet the adoption is rarely reflective. Langdon Winner’s Do Artifacts Have Politics? (1980) showed how technologies carry built-in biases that shape institutions and behaviors, often invisibly. Universities adopt digital systems as though they were neutral tools, but in fact they reconfigure the institution into something flatter, more procedural, more administratively legible, but less capable of genuine thought. The academy is not simply failing to control technology; it is being rewritten by it.

And yet the system is not something outside of us. As Alfred Korzybski noted in Science and Sanity (1933), language and symbol systems are the maps through which we live. The experience of institutions is not detached; it occurs through our own cognition, our own conversations. We live the system’s immediacy in breath and cadence, before the words we use to name it. This is why critique so often feels powerless: language is already co-opted, folded back into the very machinery it seeks to resist. The system exists not only over us but through us.

To step back, then, is not to escape but to recognize this recursive entanglement. Change does not begin in the lofty promises of institutional reform, nor in the repetition of critical slogans. It begins in small interruptions to rhythm, in alternative patterns of thought and exchange that create variance rather than replicate uniformity. Systems evolve not by declaring new futures, but by allowing the conditions for difference to propagate. The task is to find those conditions and keep them alive, even when the structures around us insist otherwise.