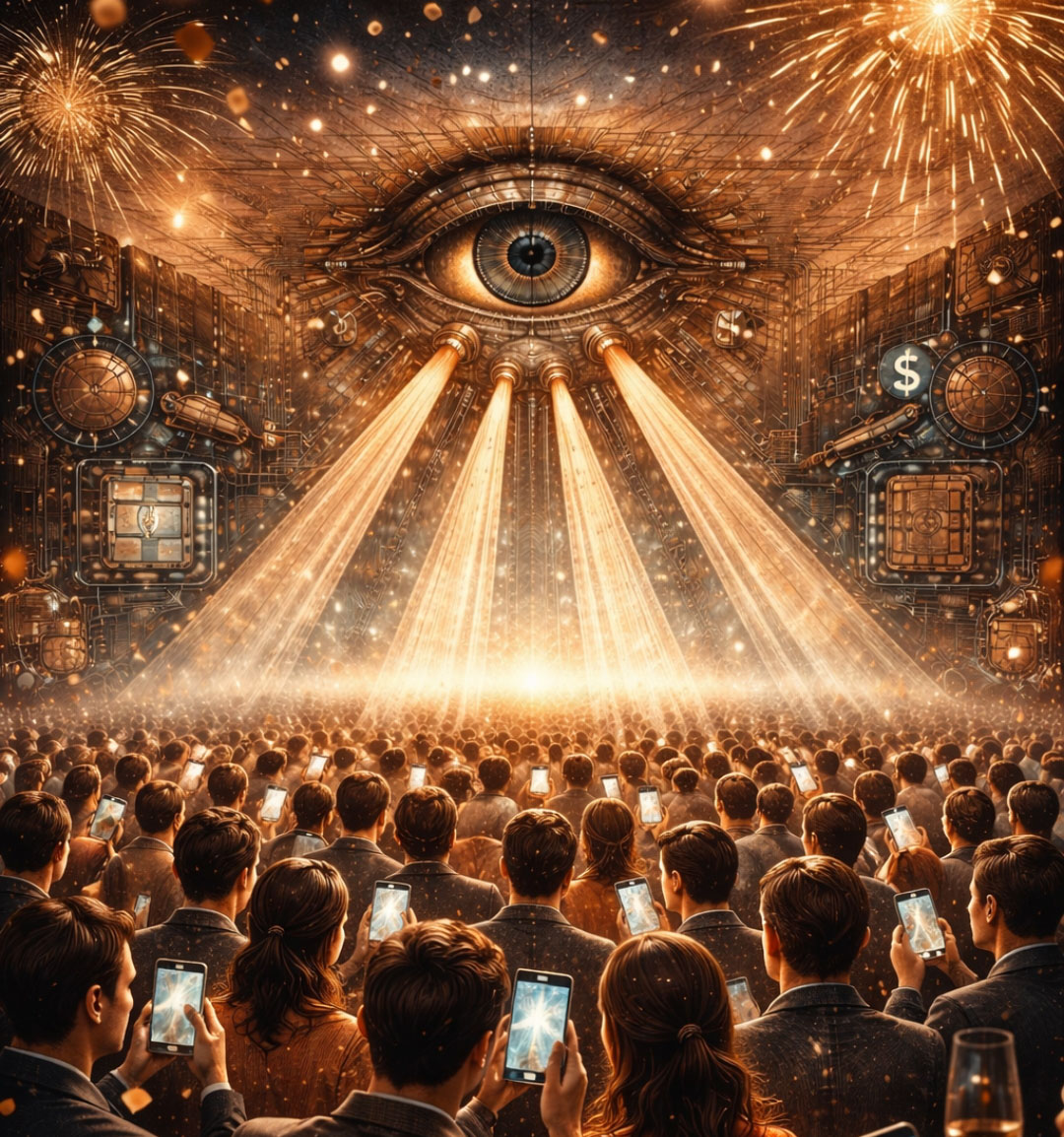

Surveillance capitalism claims to see outward, yet its deepest capture is inward. Any system that grounds authority in exhaustive data collection must internalise its own apparatus. The observer becomes the most observed entity in the field. As capture intensifies, freedom contracts. Control architectures require constant calibration and escalation, growing brittle, paranoid, and self-consuming. Power built on intrusive data does not stabilise. It oscillates, generating fear, anticipation, and pre-emptive correction. Over time, the system ceases to govern populations and begins to govern itself through them. The data subject becomes the medium through which institutional anxiety circulates (Zuboff, 2019; Foucault, 1977).

Invert the pyramid and the figure at the apex resolves not as sovereign but as prisoner. Their environment saturates with contingency. Every signal is threat. Every silence is suspicion. Every deviation implies sabotage. Cognition collapses into defensive pattern recognition. The late Roman Empire, Stalinist Russia, Maoist China, and East Germany all exhibit this progression: surveillance density increases, trust collapses, internal purges accelerate, epistemic narrowing intensifies, and policy degrades into reactive theatre (Tacitus, c.100; Conquest, 1990; Dikötter, 2010; Gieseke, 2014). The system must continually invent enemies to justify its own complexity. It cannot tolerate ambiguity, so it manufactures certainty. This is not moral failure. It is structural inevitability.

The psychology of the apex follows directly. Such figures must either absolutise their narrative or disintegrate under contradiction. Ideological closure, moral exceptionalism, and instrumental ethics become necessities. Doubt becomes treason. Complexity becomes threat. Humanity becomes noise. Studies of authoritarian leadership repeatedly show convergence toward paranoia, grandiosity, and moral disengagement under conditions of total control (Lifton, 1986; Arendt, 1951; Fromm, 1941). The system selects for these traits. Anyone unable to metabolise omnidirectional suspicion is removed. What remains is not power but a self-sealing cognitive shell, sealed against reality by its own instrumentation.

The consequence is not oppression alone, but epistemic collapse. When every signal is pre-filtered through fear, the system loses contact with the world it seeks to command. Feedback distorts. Errors compound. Corrections arrive too late. Metrics replace meaning. Legibility replaces understanding. The Soviet agricultural catastrophes under Lysenkoism, the Great Leap Forward famine, and late-stage imperial bureaucracies all display this pattern: policy becomes informational theatre while reality deteriorates beyond the system’s capacity to register it (Scott, 1998; Dikötter, 2010; Snyder, 2010). The system becomes blind precisely where it believes itself most all-seeing. The gaze of power, inverted, reveals entrapment: a narrowing corridor of allowable perception, shrinking until only compliance remains visible.

This trajectory is neither speculative nor wishful. History records the same arc across empires, regimes, and technological eras. Surveillance intensifies. Control expands. Internal contradiction multiplies. Cognitive narrowing accelerates. At a certain density of capture, collapse becomes structural. Systems that demand total transparency generate maximal opacity at the centre. Systems that seek perfect control generate uncontrollable instability. Systems that attempt to abolish uncertainty abolish their own capacity to learn (Tainter, 1988; Scott, 1998; Zuboff, 2019).

What awaits the architects of total capture is not mastery, but enclosure. They will inhabit the panopticon they construct and become its most isolated subject. The machine designed to secure dominion will convert them into its most necessary prisoner. Power, pursued as command, completes its arc as captivity. The instruments sharpen. The vision narrows. The world grows more volatile. And at the centre, the prisoner tightens their grip, mistaking enclosure for command, until history repeats its oldest lesson: power built on fear collapses inward first (Arendt, 1951; Foucault, 1977; Snyder, 2017).

References

Arendt, H. (1951) The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Company.

Conquest, R. (1990) The Great Terror: A Reassessment. London: Pimlico.

Dikötter, F. (2010) Mao’s Great Famine. London: Bloomsbury.

Foucault, M. (1977) Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. London: Penguin.

Fromm, E. (1941) Escape from Freedom. New York: Farrar & Rinehart.

Gieseke, J. (2014) The History of the Stasi. New York: Berghahn.

Lifton, R.J. (1986) The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide. New York: Basic Books.

Scott, J.C. (1998) Seeing Like a State. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Snyder, T. (2010) Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. New York: Basic Books.

Snyder, T. (2017) On Tyranny. London: Bodley Head.

Tacitus (c.100) Annals of Imperial Rome. Trans. M. Grant. London: Penguin.

Tainter, J. (1988) The Collapse of Complex Societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zuboff, S. (2019) The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. London: Profile Books.