Victor Klemperer’s The Language of the Third Reich was written under conditions that were materially, professionally, and existentially constraining. As a Jewish academic in Nazi Germany, he was excluded from public life, subject to surveillance, and deprived of institutional protection. The book did not emerge as a theoretical project but as a record: observations accumulated over time, drawn from newspapers, speeches, casual conversation, and bureaucratic language. Its form reflects this origin. It is granular, repetitive, and often understated. Klemperer was not attempting to diagnose evil, nor to construct a moral argument. He was documenting how a linguistic environment behaved when subjected to extreme political pressure, and how that behaviour propagated through everyday life.

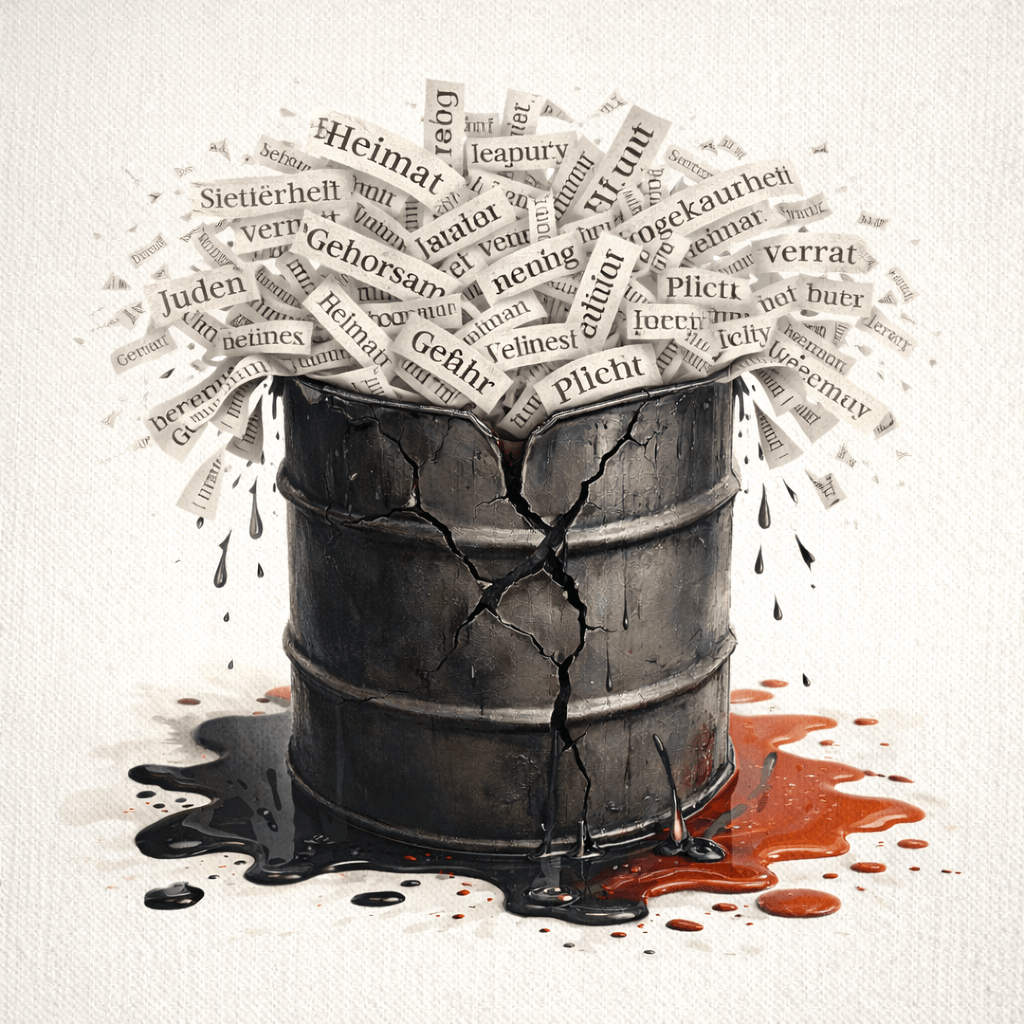

What the book exposes, structurally, is a pattern that extends beyond its historical setting. Language under such conditions reorganises itself to minimise internal differentiation. Near-perfect correlation is enforced between signal and reception, between utterance and interpretation. Words arrive already aligned with their expected uptake. Interpretation collapses into reflex. This produces a sense of certainty that can feel stabilising in contexts of fear, ambiguity, or threatened identity. But that stability is achieved by suppressing internal variation. Uncertainty and ambiguity are not resolved; they are displaced. The communicative system becomes locally coherent by exporting instability elsewhere, into designated outsiders, deferred crises, or escalating demands for enforcement.

The consequence is not simply moral failure but structural fragility. Systems that enforce near-perfect coincidence between signal and reception, between utterance and interpretation, become brittle. They lose the capacity to register error, because recognising error requires distance. Over time, the accumulated costs of suppressed difference return, often abruptly and destructively. This is why such systems tend toward collapse regardless of their apparent strength. Klemperer’s account remains relevant not because it condemns a particular ideology, but because it reveals a general property of communication under compression. When language is forced to eliminate hesitation, ambiguity, and delay, it does not become more coherent. It becomes unstable.

Categories

On the Structural Limits of Political Language

One reply on “On the Structural Limits of Political Language”

LikeLike