Introduction

In an era marked by unprecedented complexity, the quest to understand and address significant problems remains at the forefront of human endeavor. These problems—spanning disciplines such as physics, biology, mathematics, philosophy, and ecology—often defy permanent solutions. They are dynamic, evolving as we interact with them, and they challenge our conventional approaches to problem-solving.

Amidst this complexity, patterns and principles emerge that offer us profound insights. By recognizing these underlying shapes, we can navigate the intricate landscapes of our world with greater wisdom and adaptability. This exploration delves into the depths of systems theory and cybernetics, examining how they provide frameworks for understanding complex systems and the emergent behaviors within them.

We will journey through the philosophical underpinnings of these fields, drawing upon the works of thinkers like Ludwig von Bertalanffy, Norbert Wiener, W. Ross Ashby, John Archibald Wheeler, Bertrand Russell, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and others who have shaped our understanding of logic, mathematics, and the nature of reality. By integrating concepts such as the principle of least action, entropy, the Law of Requisite Variety, logical discontinuities, and the elusive “absent center,” we aim to illuminate the patterns that pervade complex systems.

This comprehensive analysis seeks not only to explain these concepts but also to reveal how they intersect and inform our approach to problem-solving in general. Through careful examination and insightful synthesis, we will uncover the subtle shapes that guide our understanding of the world and the challenges we face.

1. The Principle of Least Action: Nature’s Path of Efficiency

1.1 Unveiling the Principle

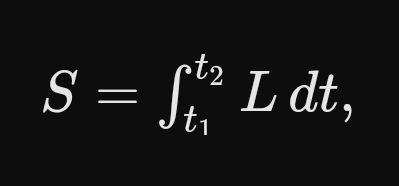

The principle of least action is a foundational concept in physics, particularly in classical mechanics and quantum mechanics. It asserts that the trajectory of a physical system between two states is the one for which the action is minimized. Mathematically, action S is defined as the integral over time of the Lagrangian :

where the Lagrangian is the difference between the kinetic energy and potential energy :

L = T – V.

This principle elegantly unifies various physical laws, offering a powerful tool for deriving the equations of motion. It encapsulates the idea that nature operates along paths of minimal “effort,” reflecting an inherent efficiency in natural processes.

1.2 Philosophical Resonance

The principle of least action resonates with philosophical notions of simplicity and economy. It mirrors Occam’s Razor, the idea that among competing hypotheses, the one with the fewest assumptions should be selected. This principle suggests an underlying order or logic governing the universe, where efficiency is not merely a physical reality but a fundamental principle.

Bertrand Russell, in his pursuit of logical foundations in mathematics and philosophy, emphasized the importance of underlying structures that govern complex systems. The principle of least action aligns with this perspective, revealing a consistent pattern in the behavior of physical systems.

1.3 Entropy and the Asymptotic Quest for Equilibrium

Entropy, a core concept in thermodynamics introduced by Rudolf Clausius, measures the degree of disorder or randomness in a system. The second law of thermodynamics states that in an isolated system, entropy tends to increase over time, leading systems toward equilibrium.

This drive toward equilibrium is mirrored in the principle of least action, where systems follow paths that minimize action, often moving toward states of lower energy and greater uniformity. However, achieving perfect equilibrium is paradoxically unattainable, introducing a tension between stability and change.

Insight: The interplay between the principle of least action and entropy highlights a universe structured around a dynamic balance between order and chaos. It reflects the human experience, where we strive for stability yet constantly adapt to change.

2. Cybernetics and Systems Theory: The Science of Complex Systems

2.1 The Emergence of Cybernetics

Cybernetics, coined by mathematician Norbert Wiener in the 1940s, is the interdisciplinary study of control and communication in animals, machines, and organizations. It examines how systems self-regulate through feedback mechanisms, maintaining stability in the face of external disturbances.

Wiener’s work was pivotal during a time when understanding complex systems became increasingly important, especially with the advent of computers and automation. Cybernetics provided a framework for analyzing how information flows within systems, influencing their behavior.

2.2 Systems Theory and Holism

Systems theory, developed by biologist Ludwig von Bertalanffy, emphasizes the holistic approach to understanding systems. It posits that the properties of a system cannot be fully understood by examining its parts in isolation. Instead, the interactions and relationships among components give rise to emergent properties—new characteristics that are not present in individual elements.

This approach has profound implications across various fields, including biology, ecology, sociology, and engineering. It challenges reductionist methodologies, advocating for an integrated perspective that considers the complexity and interconnectedness of systems.

2.3 The Law of Requisite Variety

W. Ross Ashby’s Law of Requisite Variety, a fundamental principle in cybernetics, states that “only variety can absorb variety.” In other words, the complexity of a control system must match or exceed the complexity of the system it aims to regulate.

Mathematically, if V(R) represents the variety of disturbances and V(D) the variety of responses, effective control requires that:

This law underscores the limitations of control in complex systems. Absolute control is impossible because no controller can encompass the infinite potential variations of a system. Instead, adaptability and resilience become more valuable than rigid control.

Insight: The Law of Requisite Variety highlights the necessity of alignment between a system and its controller, introducing an appreciation of uncertainty as an intrinsic feature of complex systems.

3. Logical Discontinuities and the “Absent Center“

3.1 Understanding Logical Discontinuities

Logical discontinuities represent points where traditional linear logic and predictability break down. In complex systems, these discontinuities emerge due to nonlinearity, feedback loops, and emergent behaviors that cannot be anticipated by analyzing components in isolation.

3.2 The Concept of the “Absent Center“

The “absent center” is a metaphorical construct representing an unattainable equilibrium—a state toward which systems are drawn but can never fully reach. It acts as a conceptual attractor, guiding the system’s trajectory while remaining elusive.

Philosophically, this concept echoes existentialist ideas explored by thinkers like Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus, who perceived life as an endless search for meaning in an indifferent universe. The “absent center” symbolizes the perpetual human quest for purpose and understanding.

3.3 Dynamic Equilibrium and Adaptation

In dynamical systems theory, an attractor is a set of states toward which a system tends to evolve. However, in the case of the absent center, the attractor is not static but a moving target. Systems orbit around it, continuously adjusting to maintain coherence without ever fully arriving.

This dynamic equilibrium reflects the essence of complex systems, where stability is achieved not through stasis but through perpetual adaptation. It mirrors the way biological systems maintain homeostasis and how cognitive processes continually evolve.

Insight: Recognizing the absent center and logical discontinuities allows us to appreciate the inherent unpredictability in complex systems, shifting our focus from seeking definitive solutions to embracing continuous adaptation.

4. Symmetry, Symmetry Breaking, and Emergence

4.1 The Role of Symmetry in Systems

Symmetry in physics and mathematics signifies invariance under specific transformations. It is foundational in understanding conservation laws, as demonstrated by Emmy Noether’s theorem, which links symmetries to conserved quantities like energy and momentum.

4.2 Symmetry Breaking

Symmetry breaking occurs when a system transitions from a symmetrical state to an asymmetrical one, leading to the emergence of new structures or patterns. This concept is critical in understanding phenomena such as:

Phase Transitions: In physics, when water freezes, the rotational symmetry of liquid molecules breaks, forming a structured crystalline lattice.

Spontaneous Symmetry Breaking: In particle physics, this explains how particles acquire mass through interactions with the Higgs field.

4.3 Emergent Properties and Patterns

Symmetry breaking gives rise to emergent properties—complex behaviors or structures that arise from simple rules or interactions. These properties are not predictable from the individual components but emerge from the collective dynamics.

Insight: By understanding symmetry and its breaking, we can identify patterns within complex systems, allowing us to anticipate emergent behaviors even when specific outcomes remain unpredictable.

5. John Archibald Wheeler’s Interpretations and the Nature of Reality

5.1 Geometrodynamics and the Fabric of Space-Time

John Archibald Wheeler, a prominent theoretical physicist, contributed significantly to our understanding of gravity and space-time. He coined the term “geometrodynamics,” emphasizing that the geometry of space-time is dynamic and influenced by matter and energy.

Wheeler’s famous statement, “Mass tells space-time how to curve, and space-time tells mass how to move,” encapsulates the essence of Einstein’s general theory of relativity. It highlights the interplay between matter and the curvature of space-time, leading to phenomena like gravitational attraction.

5.2 The “It from Bit” Doctrine

Wheeler proposed the “it from bit” concept, suggesting that information is fundamental to the physics of the universe. He posited that every particle, every field of force, even the space-time continuum itself, derives its function and existence from answers to yes-or-no questions—binary choices or bits.

This perspective bridges physics and information theory, emphasizing the role of observation and information in shaping reality. It aligns with interpretations of quantum mechanics where the act of measurement influences the system being observed.

Insight: Wheeler’s interpretations encourage us to consider the universe as a participatory system where information and observation play integral roles, adding layers of complexity to our understanding of reality.

6. The Philosophy of Mathematics, Logic, and Incompleteness

6.1 Bertrand Russell and the Foundations of Mathematics

Bertrand Russell, along with Alfred North Whitehead, sought to ground mathematics in logic through their work “Principia Mathematica.” They aimed to demonstrate that mathematical truths could be derived from a set of axioms using formal logical systems.

6.2 Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems

Kurt Gödel’s incompleteness theorems challenged the foundational efforts of Russell and others by proving that:

1. In any consistent formal system adequate for number theory, there are true statements that cannot be proven within the system.

2. The system cannot demonstrate its own consistency.

These theorems revealed inherent limitations in formal systems, showing that completeness and consistency cannot coexist in sufficiently complex mathematical frameworks.

6.3 Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations

Ludwig Wittgenstein, in his later work “Philosophical Investigations,” shifted from seeking logical purity to exploring the ordinary use of language. He introduced the concept of “language games,” emphasizing that meaning arises from usage within specific contexts.

This perspective highlights the fluidity and complexity of language and thought, acknowledging that rigid structures may fail to capture the nuances of human communication and understanding.

Insight: The exploration of mathematical logic and its limitations underscores the challenges in creating complete and consistent systems. It mirrors the complexities we encounter in understanding and solving significant problems.

7. Holism, Ecology, and the Interconnectedness of Life

7.1 Systems Ecology and Environmental Interactions

Systems ecology studies the interactions within ecological systems, considering organisms and their environment as interconnected components. It emphasizes:

Energy Flows: How energy is transferred through food webs.

Nutrient Cycles: The movement of elements like carbon and nitrogen.

Feedback Mechanisms: Processes that regulate ecosystem stability.

7.2 David Suzuki’s Environmental Philosophy

David Suzuki, a renowned environmentalist and scientist, advocates for recognizing the interconnectedness of all life forms and the importance of sustainable practices. He emphasizes that human activities impact natural systems in profound ways, necessitating a holistic approach to environmental stewardship.

7.3 The Gaia Hypothesis

Proposed by James Lovelock, the Gaia hypothesis posits that Earth functions as a self-regulating system, where biological and physical components interact to maintain conditions conducive to life. This holistic view underscores the interdependence of living organisms and their inorganic surroundings.

Insight: Holistic perspectives in ecology highlight the necessity of considering the whole system when addressing environmental challenges. They reveal patterns and relationships that are essential for sustainable solutions.

8. Navigating Complex Problems: Embracing the Unsolvable

8.1 The Nature of Significant Problems

Significant problems, often referred to as “wicked problems,” are characterized by:

Complexity: Multiple interconnected components and variables.

Uncertainty: Evolving dynamics that defy prediction.

Diverse Stakeholders: Differing values and perspectives.

These problems resist permanent solutions because they are embedded within dynamic systems that change as we interact with them.

8.2 Recognizing Patterns and Shapes

By identifying patterns within complex problems, we can better understand their dynamics. This involves:

Systems Mapping: Visualizing the components and their interactions.

Pattern Recognition: Noting recurring themes and behaviors.

Anticipating Emergence: Being aware of potential emergent properties.

8.3 Adaptive Approaches and Continuous Learning

Embracing the unsolvable nature of significant problems shifts our focus from seeking final solutions to engaging in ongoing processes of adaptation and learning.

Resilience Building: Developing systems that can absorb shocks and adapt.

Collaborative Efforts: Engaging diverse perspectives to enrich understanding.

Feedback Integration: Continuously incorporating new information to refine approaches.

Insight: By accepting that some problems are inherently unsolvable in the traditional sense, we open ourselves to more effective strategies that emphasize adaptability, learning, and collaboration.

9. The Special Shape: A Subtle Lens for Understanding

9.1 Subtlety and Psychological Influence

Understanding complex problems requires a nuanced approach that appreciates subtle patterns and influences. Language plays a crucial role in shaping our perceptions and interactions.

Precise Communication: Using language that is clear yet flexible to convey complex ideas.

Influential Framing: Presenting information in ways that resonate psychologically, fostering deeper engagement.

9.2 Integrating Precision and Insight

Precision in thought and expression does not preclude depth or subtlety. By being both precise and insightful, we can navigate complexity without oversimplifying.

Succinctness with Depth: Conveying rich ideas concisely.

Intelligent Engagement: Encouraging critical thinking and reflection.

9.3 The Special Shape as a Way of Seeing

The “special shape” is not a specific form but a way of perceiving and interpreting the world. It involves:

Holistic Vision: Seeing the interconnectedness of systems.

Pattern Recognition: Identifying underlying structures.

Adaptive Thinking: Being open to new insights and willing to adjust perspectives.

Insight: Cultivating this way of seeing enhances our ability to engage with complex problems thoughtfully and effectively.

Conclusion

Our comprehensive exploration has traversed the intricate landscapes of systems theory, cybernetics, physics, mathematics, philosophy, and ecology. We have examined how complex systems operate, how patterns emerge, and how understanding these patterns can inform our approach to significant problems.

Recognizing that some problems may never be permanently solved does not render our efforts futile. Instead, it invites us to adopt adaptive, holistic approaches that emphasize learning, resilience, and collaboration. By embracing the inherent complexity and uncertainty of the world, we can navigate challenges with greater wisdom and effectiveness.

The subtle shapes and patterns we have explored serve as guiding principles, offering us lenses through which to interpret and engage with the complexities of our time. They remind us that while definitive answers may elude us, the pursuit of understanding enriches our journey.

In embracing both the known and the unknowable, we align ourselves with the fundamental rhythms of the universe—continuously evolving, interconnected, and dynamic. Through thoughtful engagement, precise insight, and a willingness to adapt, we contribute meaningfully to the unfolding tapestry of existence.

One reply on “Navigating the Unsolvable: A Comprehensive Exploration of Systems Theory, Cybernetics, and the Patterns of Complex Problems”

If the maths or equation notation is off, I’m an autodidact working with LLM’s to interpolate abstract concepts. Ok.

LikeLike